You’ve done the hard work and built up a sizeable portfolio. Now, where should you invest your hard-earned cash so it keeps working hard for you?

One of the perpetual problems facing investors today is the ability to find assets with decent risk-adjusted returns without exposing yourself to the risk of permanent capital loss. The smaller is the portfolio, the harder is it to achieve reasonable returns with acceptable risk.

At this range, the amount of investable capital is significant enough to hurt investors in the event of a loss. The capital is likely to be the result of years of saving and frugal living. However, at this level, the cost of seeking professional investment advice can appear exorbitant (up to 3% of the total portfolio level). Investors are essentially stuck.

See also:

- Investing 1M: Key principles, opportunities and risks overview

- Investing 200K: How to find satisfactory returns

- Low-risk investments in Switzerland: How to get above-zero returns

Low-risk investing in Switzerland is difficult

It is worth going back to square one and to consider the purpose of investment: investing is to maximize real return whilst minimizing the chance of permanent capital loss.

Real returns mean that the financial gains derived from the asset (in the form of income yield and capital appreciation) must exceed the rate of inflation. This will lead to an enhancement in purchasing power.

Permanent capital loss is usually a result of failing to account for the risk of a particular asset, thus leading to the inability to recoup the initial capital outlay within a reasonable timeframe.

I have a rather extreme personal example.

Three years ago, I invested some spare cash into a startup company which promised to revolutionise the realty agency model. Looking at industry comparables, if it could achieve half of the scale its transatlantic competitor did then it would have delivered a 15x return on my capital.

Unfortunately, things didn’t quite work out that way. A few days ago, I received an email from the management informing me that the company had entered into administrations and it’s unlikely that investors would be able to recoup any of its investment.

Thankfully I only put in some pocket money so no hard feelings. However, this is a clear illustration of the return-capital loss paradox. Whilst the upside of this asset may be huge, it is underpinned by 2 critical risk factors:

- Capital risk: the asset in question was equity (shares) in a startup company. In the event of bankruptcy (whose probability is quite high), shareholders are last in line to receive a payout, if any.

- Liquidity risk: the shares in the company are not publicly traded. As a result, it is incredibly difficult to turn it into cash within a short time without suffering a significant loss of value, because not many people have the skills to value, let alone the risk appetite to purchase.

Investors today are confounded with these 2 critical risks. Additionally, not many possess the know-how to accurately gauge the risk-return trade-off. Consequently, this often led to poor investment decisions being made, based on gut instinct and information asymmetry.

Low-risk investment options overview

Suppose you have a 50,000 EUR/CHF/USD cash portfolio, saved over from many years. What are your realistic asset choices for investment?

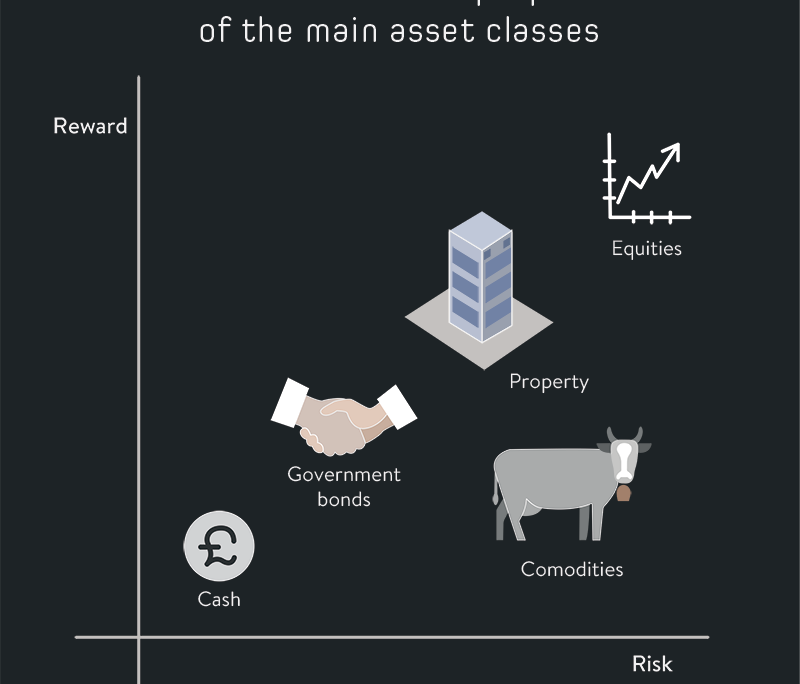

There are 3 broad asset classes available today:

- Cash

- Bond

- Equity

Risk reward ratio across different asset classes

Comparison of different asset classes by returns and risks

| Asset category | Asset | Capital return (per annum) | Income return (per annum) | Capital risk | Liquidity risk |

| Cash | Instant access savings | Nil | <1% | Nil, up to the deposit insurance coverage level | Nil |

| Cash | Termed deposit | Nil | 1-3% depending on the term and currency | Nil, up to the deposit insurance coverage level | Medium |

| Cash | Money market fund | <1% | <1.5% | Low | Low |

| Bond | Treasury bond | <2% | 0.5-5% depending on the term | Low | Low |

| Bond | Municipal bond | 3%+ depending on the grade | 2-6% depending on the municipality | Low to medium depending on the municipality (think about Detroit) | Low |

| Bond | Corporate bond | 3%+ depending on the grade | 2%+ depending on the grade | Low to high depending on the individual company | Low to medium |

| Bond | Peer-to-peer lending | Nil | 5%+ | High | High |

| Bond | Real estate bond | Nil | 3.5% – 5% | Low to medium, depending on the type of the bond and real estate | Medium |

| Equity | Dividend stocks | 4-6% | 1-2% | Medium | Low |

| Equity | Growth stocks | 10%+ | Usually less than 1%, if any | High | Medium |

As the above chart illustrates, cash and cash-like assets tend to have low return coupled with fewer risks and higher liquidity. On the other end of the spectrum, equities have high growth rate and above-inflation dividend yield. However this is counterbalanced by increased volatility and risk of capital loss.

Bonds, however, combine the above-cash return with a much lower risk profile. This makes bonds an ideal middle ground for investors with low risk appetite.

Real estate bonds become attractive under the current climate

Bond is derived from the English word “to bind”, which creates a binding instrument for one party to pay another. In the modern financial world, a bond represents an obligation for the borrower to pay the lender under terms stipulated on the bond instrument.

Here are some of the key characteristics of modern bonds:

- They do not represent ownership, but merely for the borrower to pay the lender under a specific set of conditions defined by the bond;

- They provide a fixed rate of return in the form of coupon payment (i.e. interest) to investors at regular intervals;

- Capital is redeemed at the end of the term;

- Bonds can be secured against certain assets (collaterals) but don’t necessarily have to be;

- In the event of default (borrower failing to observe the conditions of the bond), the lender has the right to seize assets and liquidate them to recoup the capital and interests, before any shareholders.

There are 2 ways to earn returns when it comes to bond investing:

- Coupon payment: each bond has a set interest rate (called coupon) that is paid out at regular intervals (monthly, quarterly or annually). This is the primary way and that’s why bonds are often called fixed income investment.

- Capital price appreciation: bonds represents an obligation between the borrower and the lender. Each bond is sold and redeemed at the face value of the bond (aka par value, usually in 100 EUR/CHF increments). It is possible, under certain situations (e.g. changing interest rate, alteration in the financial health of the issuer) for the market value to deviate from the par/face value so that you can buy it at a low price and sell it at a higher one later. In fact, just the US bond market size alone is larger than the entire global equity market combined together. However, these are highly specialized situations and retail investors tend not to personally trade bonds too often.

Bondholders have a preference over shareholders, which is manifested in 2 forms:

- Regular and uninterrupted interest payment (whereas equity dividend is an option rather than obligation);

- Liquidation preference over shareholders in the event of default.

These 2 features enable bonds to carry a different risk profile versus equity:

- Equity valuation is a product of expectation on current and future profitability;

- Bond price is more dependent on the strength of the balance sheet and the current cash flow of the business

Given that balance sheet and cash flow are much easier to measure than future profitability, bonds tend to be less volatile and are perceived to be a lower risk asset class than equity.

The special case of Swiss property-backed bonds

Until recently, property and bonds were two words only institutional investors had the privilege to be associated with. These were mega-deals that had an entry ticket in the millions of $, which were simply out of reach for most retail investors.

Yet due to lowering costs of transaction, securitisation and funding, thanks largely to technological advancement, these entry barriers are beginning to be broken down.

It is now possible to:

- Establish a limited company (special purpose vehicle or SPV) in a respectable jurisdiction within a few hours;

- Use the SPV to issue shares and bonds to potential investors to fund the purchase of a property;

- Buy properties, receive rental income and sales proceed using that SPV.

This has enabled the securitisation of the property market and thus vastly opened its access to retail investors. Investing 1 million EUR/CHF in an apartment may sound like a lot, yet when it is broken down to 10,000 shares valued at 100 EUR/CHF each, suddenly most mortal souls can start building their own property empires.

Hence we come to property-backed bonds.

An SPV that holds and lets put a property is just like any other businesses, which owns assets to generate revenues, costs for operating and financing of these assets and hopefully, it will make a profit at the end of the day.

To acquire these assets (i.e. properties), its shareholders can decide to partly fund it themselves (through equity) and partly issue bonds to borrow money from investors. They then pay out a fraction of the rental income to bondholders as coupon payment and retain the rest as profit. This way, shareholders do not have to commit a huge upfront capital payment for the project, which lowers their financial risk.

It’s a pretty sweet deal for bondholders too:

- They receive a regular and predictable return on their capital without fail -> currently yields around 3.5-5%, which is inflation-busting;

- Due to the securitisation nature of the product, the minimum investment level can start from as low as 10,000 EUR/CHF -> this significantly lowers the barrier of entry and opens up to many retail investors;

- It provides an easy and efficient manner for investors to diversify the location and class of their asset base, due to the lower entry barrier;

- Bonds are secured against the property, which means in the event of default, bondholders have the right to seize the house from shareholders and auction it off. They will be entitled to the proceeds first;

- The amount of bond as a % of the house value (loan to value ratio) is kept at a sensible level (60%), which means the property can withstand a 40% drop in market value without affecting the capital security if bondholders.

The only potential drawback between a bond of this nature versus publicly traded equities or bonds is liquidity. In other words, the ability to turn the investment into cash quickly without value erosion. Given such bonds tend to be privately issued and subscribed, the expectation is that they would be held to maturity. As a result, no markets exist for the trading of such instruments and therefore the liquidity risk is high.

In conclusion

The array of investment options available to today’s investors can indeed be confusing. However, when pierced through the haze, it is easy to see that bonds secured against valuable collaterals offer the perfect combination of inflation-adjust return and low risk to the capital.